Pluto and the Beheading of St. John the Baptist

Understanding the symbolic meaning of St. John's death through the astrological symbolism of the planet Pluto

A few months ago in the Orthodox Church, we had a liturgy commemorating the beheading of St. John the Baptist. If you don’t know the story, here is the text straight from the Gospel of Mark (Mk 6:17-29):

17 For Herod himself had given orders to have John arrested, and he had him bound and put in prison. He did this because of Herodias, his brother Philip’s wife, whom he had married. 18 For John had been saying to Herod, “It is not lawful for you to have your brother’s wife.” 19 So Herodias nursed a grudge against John and wanted to kill him. But she was not able to, 20 because Herod feared John and protected him, knowing him to be a righteous and holy man. When Herod heard John, he was greatly puzzled[; yet he liked to listen to him.

21 Finally the opportune time came. On his birthday Herod gave a banquet for his high officials and military commanders and the leading men of Galilee. 22 When the daughter of[c] Herodias came in and danced, she pleased Herod and his dinner guests.

The king said to the girl, “Ask me for anything you want, and I’ll give it to you.” 23 And he promised her with an oath, “Whatever you ask I will give you, up to half my kingdom.”

24 She went out and said to her mother, “What shall I ask for?”

“The head of John the Baptist,” she answered.

25 At once the girl hurried in to the king with the request: “I want you to give me right now the head of John the Baptist on a platter.”

26 The king was greatly distressed, but because of his oaths and his dinner guests, he did not want to refuse her. 27 So he immediately sent an executioner with orders to bring John’s head. The man went, beheaded John in the prison, 28 and brought back his head on a platter. He presented it to the girl, and she gave it to her mother. 29 On hearing of this, John’s disciples came and took his body and laid it in a tomb.

Obviously, this is a big event in the story of the Gospel and it is not surprising the Church chose to integrate it into the yearly cycle of the liturgical calendar. But something about the symbolism of this whole thing really struck me; there was some sort of underlying puzzle here that I was dying to solve. Many other martyrs in the history of the Church have been beheaded, but none of them have the event of their beheading itself commemorated. One could argue that St. John was a central character in the Gospels and his beheading is related to the story of Christ, therefore its commemoration is more related to the Gospels than the saint himself.

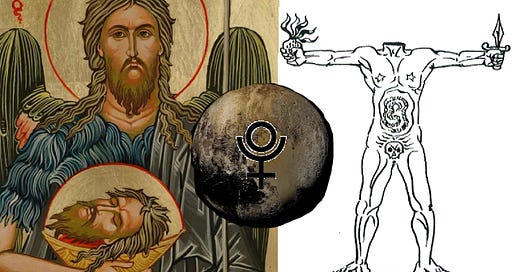

However, I believe that St. John’s beheading is crucial to his character and the specific role he plays in the church; there is one key piece of evidence that makes this point really stick out to me. If you look at many icons of St. John, he is depicted with angelic wings and is holding his own severed head on a platter. I have NEVER seen another figure in the Church depicted this way, which is what made this symbolic riddle itch my brain for months. Many saints since him have been beheaded, but you would never see them holding their own severed head. Clearly, there is something unique going on here. We can find another hint in the Kontakion of his beheading (a type of commemorative hymn we chant during each liturgy):

The glorious beheading of the Forerunner,

Became an act of divine dispensation,

For he preached to those in hades the coming of the Savior.

In the East, John the Baptist is also called “John the Forerunner”, because he came onto the scene before Christ to prepare the world for the coming of the Lord. The Church also believes that St. John died before Christ so he could go into the realm of Hades and prepare the dead for Christ’s entrance into Hades. But according to the Kontakion, it seems the beheading itself is directly tied to St. John’s ability to preach to the dead.

In Christian theology, “dispensation” can be defined as an appointment, arrangement, or favor, as by God. Another definition for “dispensation” is an exception to the general rule which has been granted by a higher authority. Given the words of the Kontakion, the Church teaches us that the beheading of John the Baptist was an event used by God to grant St. John the exceptional ability to preach to the dead in Hades. But why beheading? Why was THAT the method of execution and not hanging, drowning, or any other form?

Just how Christ’s crucifixion was not an arbitrary form of death but rather an incredibly symbolic event, my intuition screamed the same thing to me regarding St. John’s death. But what is it? What is going on here?

Oddly enough, the answer struck me like lightning when I was reading an article about Pluto entering Aquarius by Chris Gabriel from MemeAnalysis:

First, let us look at Pluto, or Hades to the Greeks. He is the god of death and the Underworld, the chthonic masculine. His symbol is the bident, a two pronged fork with a circle. I read it as an Acéphale, a headless figure. The head is the conscious ego, and the body is the unconscious. In many ways decapitation is a perfect reading of Pluto’s effect in astrology, the violent introduction of the irrational base drives. The Headless Man is operating solely on his lowest drives. The consciousness that mankind reveres is undone by our true nature. Consider the denial of Pluto the planet as a mirror to the rejection of the Freudian Unconscious. Pluto undoes our seemingly perfect, rational structures and systems with a swift coup de grâce.

I have been intensely studying astrology for the past year now, but this is the first time I had ever heard Pluto described as “a headless figure”. It makes perfect sense.

Then I began to really ruminate on the symbol of the Acéphale, the headless man. He is wielding a sacrificial dagger and a flaming heart, he has a skull over his genitals, a labyrinth for his intestines, and stars over his nipples. A rather odd symbol, but something about this cryptic figure makes intuitive sense to me. He represents the primal drives of the flesh, the underlying irrational animality of man. When there is no head to control these drives, they are blind forces that live for themselves.

I have struggled to find any solid explanation for the symbolism of this image, so I attempted to dissect it myself. The dagger represents man’s inclination to sacrifice others for the sake of survival and self-gain. The flaming heart represents the burning passion of man to manifest his own will. The starry nipples perhaps represent the desire to be glorified and elevated above the rest of mankind (why do we refer to celebrities as ‘stars’?). The labyrinth intestines represent the flesh’s endless desire to consume. The skull over the genitals represents man escaping the reality of death through sexual rapture and reproduction (it’s no coincidence that the french refer to an orgasm as ‘a little death’).

Then, it all clicked for me: St. John the Baptist is an inversion of the headless man. He is the bodiless man.

His head wasn’t cut off from his body, his body was cut off from his head.

All of these primal drives that the Acéphale represents were forsaken by St. John. His heart was on fire to fulfill God’s will, not his own. He remained celibate and did not try to run away from death through sex. He fasted from food intensely and did not indulge in overconsumption. And ultimately, he did not use the blade to engage in sacriface, but rather, he sacrificed himself to the blade. He is the bodiless head, not the headless body.

The angelic wings attached to St. John in his iconography further reinforce this idea. The angels are often referred to as the “bodiless powers” in Orthodox prayers and services. Orthodox monks are tasked with the lifelong struggle to imitate the angels while still living on earth. In a sense, they are trying to separate their heads from their bodies; they’re vocation is to become bodiless. John the Forerunner was the first to take up this task, even from birth. He wore camels’ skins, ate locusts and honey, and lived in the middle of the desert. He is the Forerunner not only to Christ, but also to the monastics who followed after Christ.

To take this image even further, one could compare king Herod to the symbol of Acéphale in this situation. What drove king Herod to execute St. John? It was all of the passions that the headless body represents. Chiefly, it was his lust for Herodias and her daughter (skull over the genitals) but it was also his desire to keep his honor in the presence of all the high-ranking officials (stars). This all took place during a banquet (labyrinth intestines) and king Herod sacrificed (dagger) St. John by ordering a soldier to go behead him (flaming heart = imposing his own will on a subordinate).

This leaves us with the question: why is St. John always holding his own head?

The divine dispensation mentioned in the Kontakion is that St. John was allowed to keep his head after it was cut off. If Hades (Pluto) is the realm of the headless, that means St. John being allowed to keep his head is a special exception granted by God. As Christ said, “Whoever seeks to save his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life will preserve it” (Luke 17:33). St John did not try to save his head, instead he gave it up. Therefore, God allowed him to keep it unto eternal life, just as Christ instituted. This is why he is holding his own head in his icons: his head is rightfully his to keep.

If Hades (Pluto) is the realm of the headless, that means St. John is the first to enter Hades and keep his head. In the Old Testament, Hades is translated from the hebrew word ‘sheol’, which means ‘the grave’ or ‘the pit’. Death was seen as this shadowy dark realm underneath the earth. It was a place of deep stillness where both the righteous and the wicked meet their final resting place. There was no one speaking in sheol until John the Baptist arrived with his head. The head represents identity, ego, the capacity to think and to speak. For the first time, the dead were hearing the voice of one crying in the wilderness, “make straight the way of the Lord” (John 1:23).

We can continue to expound on all of this symbolism by examining St. John’s entire role in the Gospels and the Church: to cut off all that is unfit for the Kingdom of God.

“And now also the axe is laid unto the root of the trees: therefore every tree which bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire.” (Matt. 3:10)

This is what baptism represents, a second birth where the old things of the past are cut off in order to enter into a new state of existence. Jonathan Pageau gives an incredible explanation of this in his video on baptism here. This is why the Church teaches us that baptism is the replacement of circumcision in the Old Testament, or rather, circumcision was a ‘type’ or ‘shadow’ of the baptism which was to come. Circumcision is quite literally cutting off the excess skin to reveal what is underneath, just like how people confessed the sins lying underneath their souls when St. John baptized them (Matt. 3:6).

Even in the icon of The Last Judgement, you see John the Baptist standing directly at the left hand of Christ. Whereas the Mother of God is seen on the right hand of Christ welcoming people into the walls of the Kingdom, John the Baptist is seen on the left hand side above those who are swept away by the river of fire flowing out of God’s throne. Jonathan Pagaeu has also expounded much on this topic of left vs. right hand symbolism. To summarize, the right hand is to bring towards and the left hand is to push away. We can even see this in Christ’s parable of the sheep and the goats:

31 “When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, he will sit on his glorious throne. 32 All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate the people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. 33 He will put the sheep on his right and the goats on his left. (Matt. 25:31-33)

There is probably more symbolism to uncover here, but I have exhausted all of the observations I have made. In my opinion, this is a great example of how studying symbols that are not Christian can still lead us to a greater understanding of the truth through Christ. Because Christ IS truth, and all things that are true are of Him. By studying the inverse of St. John the Baptist, which is the Acéphale, we can actually understand more about St. John as a character in the Bible. And by studying the symbolism of the planet Pluto (‘Pluto’ merely being the latin translation of ‘Hades’), we can gain more appreciation for St. John’s amazing act of bringing his head with him into the realm of the dead in order to prepare a way for Christ.

Fascinating read. It's interesting to note America going through it's first Pluto return, seems like she is experiencing a baptism of sorts.

great article, its always fun to see the connections